Your body is your voice is your body

Somatic education for singers

Singers and voice teachers consistently search for one of the "holy grails" of efficient voice production—improved posture:

What is it, and how can we readily find it?

I am a singer and vocologist with a congenital defect in my left temporomandibular joint (TMJ); I have no disc present to cushion the joint from the impact of daily use, let alone the stresses of regular singing.

Throughout my life, I have had issues with my jaw—it started clicking at age 9. I tried braces, acupuncture, physical therapy, a TMJ splint (for 25 years), a night guard, massage, yoga, muscle relaxants, a soft food only diet (a nightmare for a salad lover like me), and the list goes on and on. At no point did I consider stopping singing, but the tension issues have consistently been an interference in my personal and professional life.

Everything came to a head in spring of 2019 as I began preparing for a planned recital.

I had not sung for a couple of months, and when I began practicing, I had a distinct wobble in my middle voice and my voice just stopped making sound a little bit higher. I was only 46. I should not sound 40 years older than my age!

Full of fear and trepidation, I went to my laryngologist and got a videostroboscopic exam of my vocal folds. They looked healthy (which was a relief), but I had extreme anterior-posterior compression and protective posturing of the larynx—classic symptoms, along with my phonation issues (those pitches where I couldn’t make sound, or at least not sound I intended), of muscle tension dysphonia (MTD). The standard prescription of voice therapy was denied by my medical insurance because my issues did not "significantly impede" upon my daily life.

Sidebar: Voice issues I have personally experienced, 2010-2021:

a congenital defect in my jaw led to a lifelong need to care for TMJ/jaw tension,

excessive reflux assisted in my developing a medial vocal fold cyst (like a blister--I started sounding like a cartoon duck quacking when I tried to sing), resolved by voice therapy and behavioral changes, and

muscle tension dysphonia, caused by muscular holding patterns protecting my jaw, which created severe interruptions with my desired vocalizations--resolved by my training in Bones for Life® and exploring other somatic techniques such as the Feldenkrais Method®.

At the same time, my jaw became tighter and tighter until I was in constant pain. I went to a TMJ specialist who placed me on muscle relaxants and a soft food diet. I also got a 3D x-ray and was diagnosed with osteoarthritis in both temporomandibular joints. After two months, I was not progressing at all—the pain and the voice issues were still there. The next step, I was told, were regular Botox injections to paralyze the masseter (chewing) muscles. Of course, this use is not covered by insurance.

I decided that if I had to pay a significant amount of money out of pocket, I wanted to choose my own intervention, and paralyzing myself was not my choice. I chose to pursue Feldenkrais® Functional Integration (FI) lessons in person, inspired by my experiences at the 2018 PAVA/VASTA joint conference: Soma & Science: Bridging the Gap in Interdisciplinary Voice Training.

After five months of FI training, and an additional several months of singing voice lessons with Feldenkrais practitioner Robert Sussuma, application of these principles resolved the majority of my MTD.

But, as a voice teacher, I could not justify turning all voice lessons I teach into lengthy Feldenkrais® lessons (nor am I certified to do so). I needed simpler and more immediate ways to apply somatic principles in the voice studio.

Enter the Feldenkrais Awareness Summit of May 2020 where I encountered Ruthy Alon’s Bones for Life® program.

Ruthy Alon is the creator of multiple programs under the header “Movement Intelligence: Movement Nature Meant,” which includes the Bones for Life® program. In 1967, Alon was in the first group of thirteen students to be trained by Moshe Feldenkrais to teach his program of Functional Integration. She followed him to the United States in the 1970’s and assisted him in his first professional trainings. As Alon aged, she began to delve more deeply into stability issues and bone loss and was inspired when NASA showed that loss of bone density is a reaction of the organism to the conditions in which it lives. She posited that bone density could then be replenished in response to encounters with gravity, achieved through guiding the skeleton to navigate to an efficient posture.

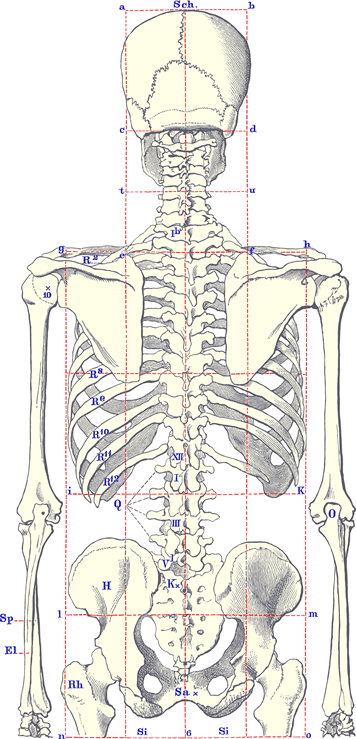

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SkeletonBodyBack.gif {{PD-1923}} – published before 1923 and public domain in the US. (Leipzig verlag von veit & Comp. 1910, page 559)

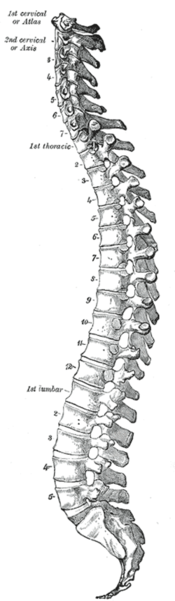

A universal concept in developing ideal voice use lies around the need for the singer to have an aligned skeleton—the need to address posture and alignment is present in just about every textbook on voice pedagogy, and even more so in the past fifteen years.

In Bones for Life®, I find that the focus on active alignment for stability perfectly complements the needs of the singing body. Additionally, the processes are frequently brief, allowing for easy integration into a voice lesson, even daily life.

Vertbral Column_Lateral View-Gray's 1918.gif PageURL: http://www.bartleby.com/107/illus111.html Gray, Henry. Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1918; Bartleby.com, 2000. www.bartleby.com/107/. [Date of Printout]. Terms of Use: http://www.bartleby.com/sv/terms.html

Two major concepts:

These processes are not exercise—minimal effort (never greater than 20%) is to be expended.

If any sense of pain or discomfort is encountered, participants are encouraged to back off and to expend only 2%, or even just imagine the movements.

I have found BFL processes invaluable for both me and my students, especially as I taught solely online voice lessons throughout the pandemic.

My students were able to find ways to be in touch with their bodies in new ways, and all found substantial improvement in their vocal quality.

The best part is that these opportunities can be short enhancements of the singing lesson and do not need to detract from the other necessary components of a lesson.

As needed, we can spend lesson time on longer and more complicated components, but most are simple enough to incorporate at least part of a process into every lesson or student practice session.